| |

21. The Sma Tawy vignette: a historic overview

Because the Sma Tawy

vignette has been depicted very often (and often on stone, where it

had a better chance of survival), its evolution over time can be

followed in considerable detail. And because the heraldic plants of

Upper and Lower Egypt are always part of this vignette, the evolution of

their appearance can here be followed too.

|

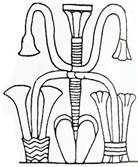

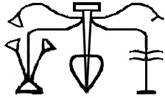

The earliest

extant example of a Sma Tawy comes from a stone

vessel from the time of king Adjib, one of the last kings of the 1st

dynasty. Although the depiction is not intact, we can still

recognize that it consisted of the hieroglyph smA between a

papyrus plant and a sedge.

(Drawing

based on

P.D. IV, n.

33, after a copy on the website of

Francesco Raffaele. |

|

As already mentioned, the hieroglyph smA

depicts a windpipe and lungs. The lungs are here shown with great - if

not disturbing - accuracy: carefully showing the lobes. (Actually, there

should be two lobes on the left, and three on the right, but who’s

complaining?)

The plants do here not yet exhibit the later

canonized forms. The one on the left is a papyrus

plant

with

buds instead of opened flowers. The one on the right does not yet show

the flowers

that later appear at the tips of the stalk and twigs. (In

this early phase of the script, the signs M23 (the sedge) and M26 (the

flowering sedge) are not yet consistently distinguished in other uses,

either.)

Although the elements in this

depiction

are not yet tied together, it is still obvious that

this

is not just a writing of the phrase “Uniting the Delta and the Valley”.

In such a writing, the sign smA (to unite) would not have stood

in the middle. It is therefore certain that this is even now a

monumental representation: one that we can already term a vignette.

|

The next

example in our little collection comes from a stone vessel that carries

the Horus name of king Teti (1st king of the 6th

dynasty). It is however so decidedly archaic in execution, that this

is either a re-used early dynastic vessel, or a case of conscious

archaizing on the part of a 6th dynasty artist. (Both

practices are well attested.)

(From

Steingefässe, page 60. Reproduced with permission

from the

publisher.) |

|

|

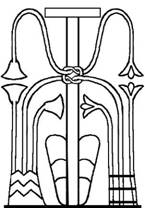

In Hierakonpolis I

(available on the website of

archive.org), we find this image from a granite vase from

Khasekhem (thought to be the same as Khasekhemwy, last king of the 2nd

dynasty). This time, the plants are tied together around the

Sma-sign. Unfortunately, they are too sketchily drawn to distinguish

between them - let alone identify them.

(Note the horizontal

striping on the windpipe, indicating its cartilage rings.)

|

|

That the Teti-depiction we just saw (of

would-be

6th dynasty origin) is definitely

anachronistic

becomes totally evident when we compare it with the next picture from

the 4th dynasty. It exhibits all the confidence of a fully

matured art.

|

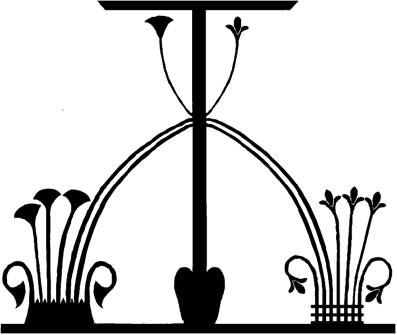

It comes from the

side of the throne on one of the famous seated statues of king Chefren from

his mortuary temple at Gizeh. To the left are the easily recognizable

papyrus plants. A new element is, that they rise from a pool. Which

is not exactly out of character for an aquatic plant, but

nevertheless a bit surprising, for so far they were seen growing

from a hump of clay.

(StS Art,

page 94) |

|

The plants to the right also have a new element to

them: they are bound together at their lower end, with three horizontal

bands, suggesting that these stalks are not too firm, or cut off. But

what’s more important: they look decidedly different from the sedge -

flowering or not. So what is it? It can hardly be a lotus: if we compare

these flowers (if that is what they are) with the Old Kingdom renderings

of the lotus that we have seen before

in section

10,

we see not much of a resemblance.

|

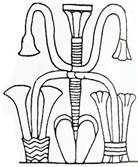

When we get no more

than just two kings further down the road, we find that under

Mykerinos again the flowering sedge was used for Upper Egypt.

Compared to the rather robust design under Chefren, this one

shows a consious attempt towards refinement.

(Based on Plate 17 in

Schäfer.

Left-right reversed, to match the other

examples.) |

|

Any study of the development of a decorative motif

during the Old and Middle Kingdoms is seriously hampered by the scarcity

and one-sidedness of the available material. In the way of temples and

temple reliefs, very little has survived from these periods. Just what

we are missing

becomes painfully clear through those few chance

survivors that we happen to have. Some of these come from the causeways

that were part of the pyramid

complexes of Cheops (4th

dynasty) and Unas (5th dynasty), but most are from Niuserre’s

sun temple at Abu Gorab (also 5th dynasty).

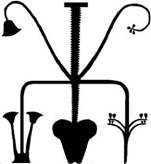

A relief from the latter location shows the king

seated on a throne, while the throne

itself

stands on a platform. The side of the platform is decorated with the

following

Sma Tawy:

(Based on Plate 20 in

Heinrich Schäfer: Principles of Egyptian art. Left-right

reversed, to match the other

examples.)

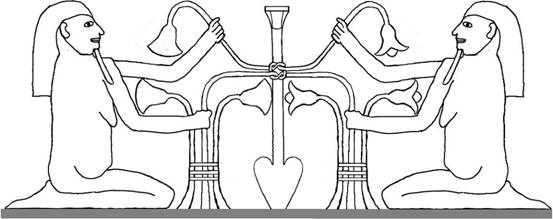

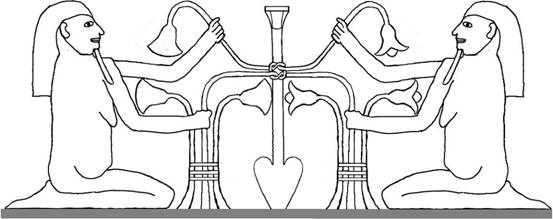

This is the oldest example known to me of a Sma Tawy

in which the personifications of the Two Lands attend. The exploring,

hesitant style is

apparent: they don’t yet have the identifying tufts

on their heads, and their hands are holding the stalks as if not

really

knowing what to do with them.

This is also the first time that we see the lotus as

papyrus’s opposite number. Note furthermore that

here, both

plants are held in place at

their lower ends by horizontal bands: an

experiment

that was later abandoned again.

The Palermo Stone is a fragment of a monument that contained the royal

annals from the 1st till mid-5th dynasty. The

monument was made in the 5th

dynasty, and the “handwriting”

of the glyphs is from that period. So although the vignette of Sma Tawy

is here already in evidence in what is probably the second reign of the

1st dynasty, its execution is from the 5th

dynasty.

|

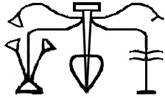

Every year in these

annals is named after a certain event, or events. The 1st

year of a reign, the year of coronation, is always described as:

“Year of uniting the Two Lands”, graphically rendered as follows: |

|

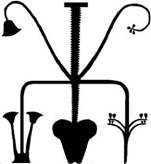

The signs on the Palermo Stone are only about 1 cm in

height, lightly cut on hard stone, and rather worn, too. Most

authors will therefore “ interpret”

to some extent their

rendering

of such signs - as indeed I have done here, too. There is obviously some

risk involved in this practice. Just how much risk is aptly illustrated

by the following.

In

Von Beckerath’s Chronologie,

the author rightfully pays

considerable

attention to the Palermo Stone. The illustrations on pages 15 and 16

however give a really gruesome “reconstruction”

of the Sma Tawy’s on this monument.

|

(sic!) |

First of all, the

upper flowers have changed sides above the knot that ties them

together. Much as this is in agreement with our views on

logic and composition, the ancient Egyptians never depicted

it like this. Furthermore, the Upper Egyptian plant is at the bottom

end a sedge, while on the upper side it’s a lotus: really a fine

piece of genetic engineering. |

After the Old Kingdom, only one new element seems to be added to the Sma

Tawy: that of the patron gods assisting, as

alternative for the

personifications

of the Two Lands. This is

however

a conclusion, based on the surviving evidence: it seems entirely

possible that this feature was already in use during the Old Kingdom.

For the rest, the further evolution of the vignette

just followed the general trend of the times: sober, forceful stylizing

in the Middle Kingdom, refined elegance in the New Kingdom.

|

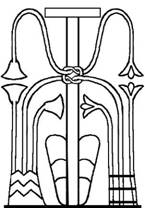

Here is a Middle

Kingdom example from a festival relief of Sesostris III (12th

dynasty). This compact, rectangular conception remains a classic -

especially on the sides of thrones of divinities. The lower parts of

the two plants are treated just like in the Chefren example that we

saw earlier: the papyrus rises from water, while the lower ends of

the lotus stalks are supported by bands of rope or the like. In

monumental uses, this remains the preferred treatment for the lower

parts of the plants, while in the hieroglyphic record, with its

greater need for stylizing, both plants are always depicted emerging

from a hump of clay. |

After a

photograph in

L&H

104-5.

|

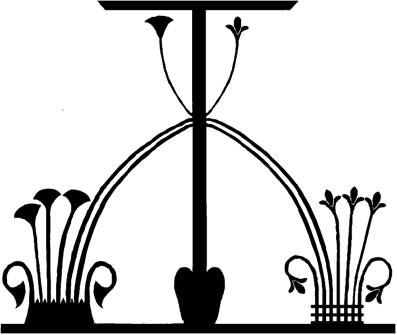

In the New Kingdom, new levels of elegance and

sophistication are attained. We have already seen an example from a

colossal statue of Ramesses II at the temple of Luxor. If we

remove

the personifications of the Two Lands, and

eliminate the color, what

remains is the refined design.

From the side of a colossal

statue of Ramesses II, Luxor Temple.

(Left-right reversed.)

Had we not followed the foregoing historic overview,

we would have been rather puzzled by the papyrus’s “pointed cake”, and

the lotus’s “fencing”. Now we understand that the

fencing

is really three bands holding the cut-off stalks of the lotus

together,

while the points represent the ripples of the water from which the

papyrus emerges.

This came to be the

preferred treatment of the plants in the Sma Tawy - and there may be a

good deal of logic behind this. The whole idea was, to show the stalks

of both plants being tied together. For papyrus, this did not pose a

particular problem. Papyrus grows in the water, but the largest part of

its stems stand above the surface. So papyrus can be shown in its

natural appearance: rising from the water. The stalks of the lotus

however, are normally invisible: hidden below the water. So in order to

bind the stalks of papyrus and lotus together, those of the lotus had to

be cut below the water, and brought to land. Above water however, the

stalks have lost their footing, and need to be bound together to keep

them in place. Hence the three bands.

The next example is again from Ramesses II, this time

from the great hypostyle in the Amun temple of Karnak. Here we see the

two patron gods performing the act: this time

with

Thoth for Upper Egypt. The design of the plants so closely resembles

that of the Luxor colossus, that it may have been drawn by the same man.

Instead of alluding symbolically to the king by way of his name, he is

now depicted in the flesh above the Sma-sign.

Ramesses II, with the gods

Thoth and Horus.

From the inner (south) wall of the Great Hypostyle in the Amun temple of

Karnak.

Back to start

Previous

Next

Thumbnails

|

|