From the pages of every illustrated book on ancient

Egypt - especially the modern glossy ones - the lotuses and papyri more

or less jump

right into your face. Small wonder: they were among the ancient Egyptian

artist's favorites.

For the time being, we will confine ourselves to depictions of lotus and

papyrus in other uses than as the heraldic plants of Upper and

Lower Egypt.

On the walls of temples and tombs, we see lotus

flowers decorating offerings: wound around earthenware or faience water

vessels, lying on top of piles of food - or as offerings in their own

right.

|

We see ladies at

a banquet, with lotus flowers in their hair, or holding a lotus

flower in their hand, breathing in the wonderful scent. We see

goddesses carrying a staff, crowned with a papyrus flower. In the

catalogue of daily life that covers the inner walls of Old Kingdom

mastabas, papyrus is shown as the raw material from which all

sort of things are made: boats and rafts, rope and paper.

The harvesting of papyrus plants is also depicted:

men are bowed down under heavy loads of gigantic stems. |

The goddess Isis, carrying a papyrus scepter. Hieroglyph C161 from

the Hieroglyphica.

|

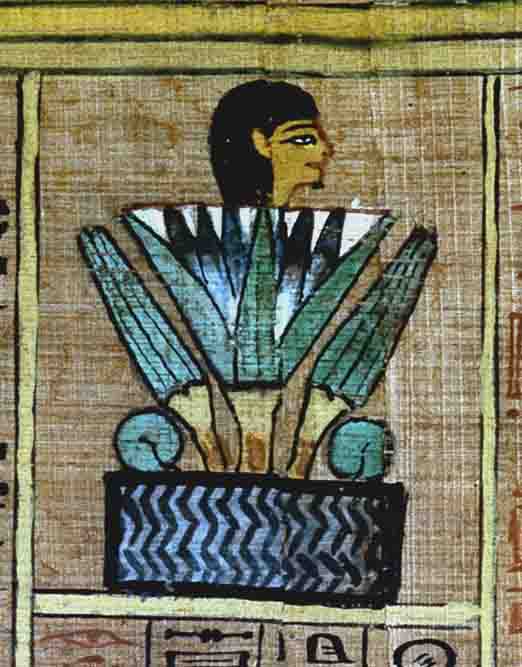

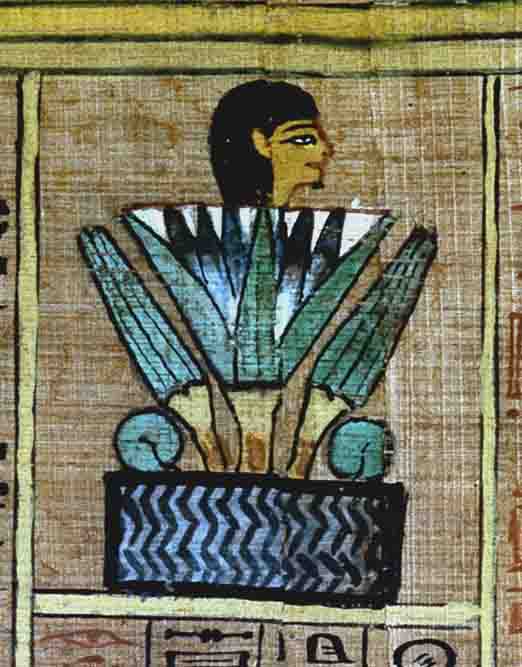

Below is part of the vignette of Spell 81A from the Book of the

Dead.

|

|

It comes from the Book of the Dead

of Any, now in the British Museum. Being one of the finest

surviving manuscripts, it is reproduced frequently.

We see the head of Any, rising from a lotus flower. This image

refers to a myth in which the Sun god is born from a lotus flower.

By inserting his own countenance in this image, Any hopes to share

the fate of the Sun god - and to live forever.

Comparable

depictions of lotus flowers from the same manuscript can be found

in several other vignettes, such as those of Spells 9 and 17.

© Trustees of the

British Museum |

Both the shape of the flower, and the color of its

petals, clearly show this to be the blue lotus.

|

Significant from an iconographic point of view

are the small white triangles between the points of the petals. As

I’ve mentioned before, the ancient Egyptian artist was primarily

focused on working with a shape’s outline. Adjacent, you see the

traditional form for the flower of the blue lotus: |

|

It is delineated on the top by an arc. When the

artist fills in the drawing with color, he must ignore the top elements,

between the points of the petals, for they do not belong

to the flower itself: they represent empty space. A modern artist would

not have added the arc, thereby letting the space between the points of

the petals stay a part of the background. The Egyptian draftsman however

was committed to the use of simple, yet effective outlines. So he filled

in the surplus space within the outline with white, to indicate that it

was in fact empty space. This makes it a variant of the black that on

statues is used for the space between the two legs, or between the arms

and the torso (what Aldred calls “negative space”: see

Aldred EA).

Above is a detail from the Anubis chapel in

Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple at Deir el Bahri. You see a rack with four

water jars, each with a lotus flower on top. Again, the shape of these

flowers is that of the blue lotus. We now recognize the white as

representing the “empty space” within the conventional flower's outline.

The missing blue and green pigments have either faded, or fallen off.

From the same chapel. Here we see papyrus and

lotus flowers themselves as offerings in their own right. The lotus

flowers in this example are of the white variety: note the wider, more

open shape of the chalices. The hand to the right is that of the

recipient: the god Amun-Re.

|

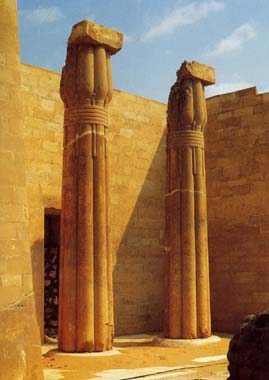

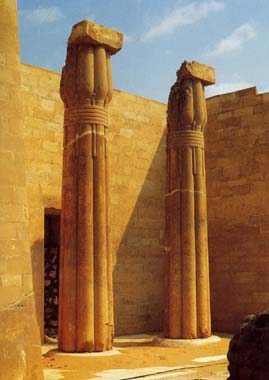

In temples. many columns were shaped as

(bundles of) papyrus stems, crowned with either buds - single or

multiple - or open flowers. Stone columns in lotus-form

were rarely used - and only in private tombs. The first of these

that we are aware of are the two magnificent columns of the

entrance portico of the mastaba of Ptahshepses at Abusir (5th

dynasty). Later on, we find lotus columns occasionally in Middle

Kingdom rock-cut tombs.

The mastaba of

Ptahshepses at Abusir

(5th dyn). © W. de Jong

From "De

Ibis" 2005, page 9. |

|

Both lotus and papyrus also figured frequently in

the houses of the well-to-do. There, the columns were of wood, and next

to papyrus columns (as well as several other types), we here encounter

quite a few lotiform ones. Both lotus and papyrus flowers also decorated

cosmetic appliances such as wooden spoons for unguents. Handles of

hand-held mirrors often had the shape of a papyrus stem with flower.

The same motifs decorated pieces of furniture, too: see e.g. the wooden

armchair of Hetepheres, mother of king Cheops (4th dynasty).

The sturdy, powerful design of bent papyrus flowers under the arm’s

rests is an echo of the times (StS Art 88).

Likewise, a particularly graceful alabaster lamp in the shape of three

lotus flowers from Tutankhamun’s tomb, reflects the subtlety and

refinement of New Kingdom high court taste. In the Third Intermediate

Period, refined drinking goblets were made of faience, using the shape

of a white lotus (wide, cup-like) or that of a blue lotus (narrow,

beaker-like). (Some very fine specimen of both types in the Myers

Collection, at Eton College.)

|

The white lotus |

The blue lotus |

Papyrus |

Characteristic renderings

of lotus and papyrus in the arts.

|

A capital in the shape of an open papyrus flower

(Karnak, the central aisle of the great hypostyle, early 19th

dynasty)

<== Papyrus bundle

columns, with capitals in the form of closed papyrus buds. (Luxor,

court of Amenhotep III, 18th dynasty) |